The rivalry of Eumenes and Antigonus lit up the eastern domains of Alexander the Great with intense and large-scale fighting in the years following the legendary king’s death in 323 BC. An underdog at the beginning of the Successor Wars, Eumenes remains a beguiling character whose battlefield victories saw him arrive at the brink of total power.

Though he had modest origins, Eumenes had served as secretary to Alexander, and his father Philip II before him, and acquired authority and prestige through his control of the conquerors’ intelligence and correspondence. His aristocratic opponents sought Eumenes’ death almost from the off, but Eumenes prevailed. Yet with the death in 319 BC of Antipater, the elderly steady hand entrusted by Alexander to rule in Europe, the general Antigonus saw an opportunity to take control of the empire himself. It set him on a direct path to confrontation with Eumenes.

Besieged at Nora

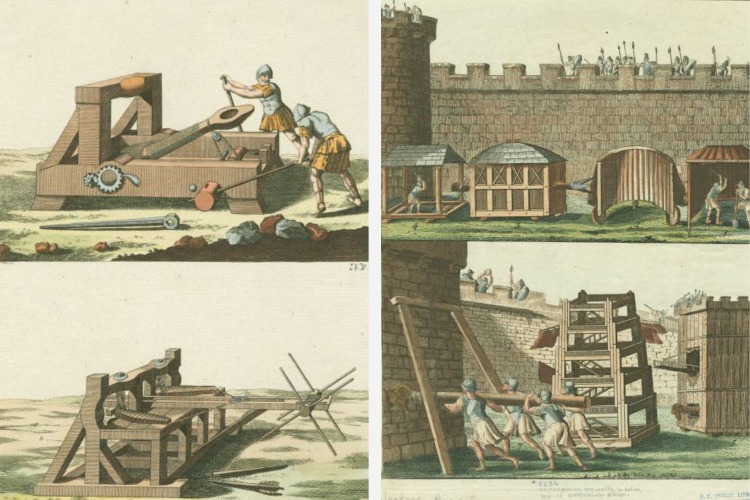

In 319 BC Eumenes had been defeated by Antigonus at the Battle of Orkynia in Cappadocia, after which he had retreated and taken refuge in a virtually impregnable stronghold called Nora. Recognising Eumenes’ proven ability to command, Antigonus is supposed to have made an offer to Eumenes to instate him as one of his own officers. Eumenes may have sought better terms and in any case would have been well supplied to wait it out. Soon the death of Antipater would throw his opponents’ plans into disarray.

1810 depictions of ancient siege warfare.

Image Credit: New York Public Library / Public Domain

But Antigonus was not the only powerful Macedonian who desired Eumenes as an ally. Back in Macedonia, Antipater’s successor, Polyperchon was also eyeing his support. At that time, Polyperchon’s position was in jeopardy. Antipater’s son Cassander, furious at not being labelled his father’s successor, had started gathering an army to confront Polyperchon. He sailed over to Asia Minor, to petition Antigonus.

Antigonus agreed to Cassander’s offer of an alliance. Polyperchon was now desperate. Antigonus was then the most powerful commander in the empire, with an army of almost 70,000 men. Polyperchon looked to Eumenes.

Kings’ General

Polyperchon sent a messenger to Eumenes in Cappadocia with an irresistible offer. If he were to break with Antigonus, the new regent offered Eumenes the title of ‘King’s General’ in Asia. Polyperchon offered him access to the vast royal treasury at Cyinda and even more auspiciously, command of the Silver Shields, Alexander the Great’s veteran Macedonian infantry guarding the treasury.

Eumenes abruptly headed east to Cyinda. There, as promised, he gained access to the royal treasury and the formidable Silver Shields. Eumenes’ war with Antigonus was back on.

The war re-starts

Antigonus was furious. Thanks to Polyperchon’s offer, he now had a new great threat in the east. Abruptly, his plans to invade Macedonia were put on hold and gathering a large army, he headed east once more in pursuit of the Cardian. Yet by the time he reached Syria, Eumenes had already departed. He had headed further to the east, keen to enlist the aid of the eastern governors against Antigonus.

Near Susa, Eumenes met with many of these satraps, already united with their armies. Most notable among these men was the Macedonian Peucestas, a former bodyguard of Alexander, friend to Eumenes and the governor of Persia. There was also Eudamus, who had come from India with a large force of elephants.

The Battle of the Coprates River, 317 BC

Meanwhile, Antigonus received reinforcements at Babylon from two fellow Macedonian generals, Seleucus and Peithon, and went in hot pursuit of Eumenes. In the summer of 317 BC, their forces clashed on the eastern bank of the Coprates River, now known as the Dez River in Iran. While Antigonus’ forces were in the midst of crossing, Eumenes led 4,000 infantry and 1,300 cavalry towards the river, and charged.

The forces of Antigonus that had reached the other side, some 6,000 men, were taken completely by surprise. Soon that part of Antigonus’ army routed. Eumenes had won a small but clear victory, taking over 4,000 of Antigonus’ men prisoner. Unable to cross, Antigonus was forced to head north, around the Zagros Mountains. Fresh from this victory and with Antigonus off his back, Eumenes now planned to turn around, returning with his large army towards the Mediterranean.

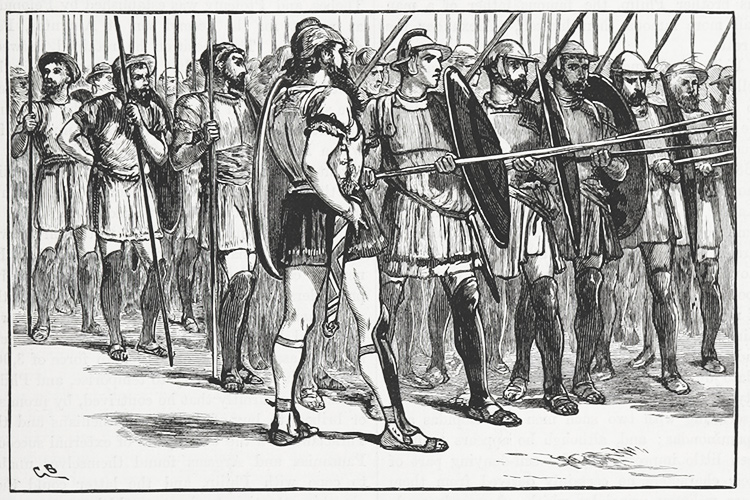

The Macedonian phalanx, from “Cassell’s Illustrated Universal History” (1893).

Image Credit: British Library / Public Domain

Yet his eastern allies, most notably Peucestas, refused to comply. They feared that if they headed west, Antigonus would ravage their provinces. The eastern provinces were some of the richest lands in the empire, after all. Relenting, Eumenes continued east to Peucestas’ provincial capital of Persepolis. Antigonus circumnavigated the Zagros Mountains and was again advancing on Eumenes. Eumenes marched his forces from Persepolis to meet those of his rival. On the plains of Paraetacene, their forces clashed once again.

The Battle of Paraetacene, 317 BC

At Paraetacene, Eumenes deployed his army at the bottom of the plain. His force numbered just over 40,000 men, including 35,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry and 114 elephants. On his left, Eumenes placed over 3,000 of his cavalry. Then in his centre, he then placed his mercenary infantry, 5,000 troops trained in the Macedonian manner and finally, in the most prestigious place of the infantry line, the Silver Shields.

On his right wing, Eumenes placed his heavy cavalry, including both himself and Peucestas. Finally, Eumenes spread his elephants along the length of his line, with light infantry in between. Facing Eumenes, Antigonus’ army lay on a slight elevation to one side of the plain. His army was slightly smaller than that of Eumenes: 28,000 infantry, 8,500 cavalry and sixty-five elephants. On the left wing, he deployed his light cavalry: most notably a thousand agile horse archers from Parthia and two thousand expert Tarentine cavalry. These were placed under the command of Peithon.

Listen Now

Listen NowNext to them, Antigonus placed his mercenary infantry, followed by 8,000 mixed Asian troops trained in the Macedonian manner and finally his 8,000 Macedonians. On his right wing, Antigonus placed his finest cavalry, the Companions, under the command of his son Demetrius, with himself furthest to the right. For his elephants, Antigonus placed most of them in front of his infantry line, facing those of Eumenes, with light infantry interspersed between them. Deployed in such a manner, Antigonus advanced his army at an angle. He moved his stronger right wing forward, keeping his lighter left wing further back.

Peithon’s charge

Sensing an opportunity for personal glory, Peithon decided to take matters into his own hands. He ordered his light cavalry on Antigonus’ left to advance against those facing them. Equipped with swift mounts and deadly missiles, these horsemen then rained arrows and javelins down on the opposing elephants and cavalry. Eumenes responded by sending a portion of his light cavalry on his left flank over to his right, chasing away Peithon’s light horsemen from the battle.

Meanwhile the infantry phalanxes had collided, and a desperate struggle was underway. Finally, the great experience of Eumenes’ silver shields shone through. Their unit had fought in the campaigns of both Philip II and his son Alexander; their skill was unmatched, crushing Antigonus’ opposing infantry easily. Much of Antigonus’ army was now in retreat. But the one-eyed general himself refused to withdraw. Seeing an opening on Eumenes’ left, he charged with his elite cavalry into the side of this force, causing panic. Eumenes’ left wing collapsed.

The rest of his army however was still intact and came to fend off any further attacks from Antigonus’ remaining forces. The battle ended with both sides claiming victory, yet it was Eumenes who had come off better. He had lost just over 500 men in the encounter; Antigonus on the other hand, had lost almost 4,000.

The war continues

Eumenes marched further east, to the rich lands of Gabiene while Antigonus returned to Media. Antigonus knew that the odds were now stacked against him; his losses at both the Coprates river and now at Paraecatene meant that his army was now notably smaller than that of Eumenes. He therefore attempted to outwit his foe with a surprise attack. Rather than waiting to restart campaigning next summer, Antigonus marched his army in the winter of 316 BC, through a harsh wilderness, hoping to surprise Eumenes.

Unfortunately for Antigonus, the plan was foiled and Eumenes managed to organise his forces on a nearby plain, awaiting the next battle. And so it was that in the winter of 316 BC, the final great clash between these formidable generals was to take place. It would decide the Second War of the Diadochi.