On 22 November 1963, the world was shocked by the news that US President, John F. Kennedy (JFK), had been fatally shot during a motorcade in Dallas. He had been sitting in the backseat of an open-top car beside his wife, Jacqueline ‘Jackie’ Kennedy.

In the hours, days, months and years following the assassination of her husband, Jackie Kennedy cultivated an enduring myth around her husband’s presidency. This myth was centred around one word, ‘Camelot’, which came to encapsulate the youth, vitality and integrity of JFK and his administration.

Why Camelot?

Camelot is a fictional castle and court that has featured in literature about the legend of King Arthur since the 12th century, when the citadel was mentioned in the story of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Ever since, King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table have been used as a symbol of courage and wisdom in politics.

For centuries, King Arthur and Camelot have been referenced by monarchs and politicians hoping to align themselves with this famed myth of a romanticised society, typically one led by a noble king where good always wins. Henry VIII, for example, had the Tudor rose painted on a symbolic round table during his reign as a way of associating his rule with the noble King Arthur.

After the death of JFK in 1963, Jackie Kennedy once again employed the myth of Camelot to paint a romanticised image of his presidency, immortalising it as pioneering, progressive, even legendary.  Listen Now

Listen Now

Kennedy’s Camelot

In the early 60s, even before his death, Kennedy symbolised power and glamour in a way that American presidents had not before. Both Kennedy and Jackie had come from wealthy, socialite families. They were both attractive and charismatic, and Kennedy was also a World War Two veteran.

Additionally, when he was elected, Kennedy became the second-youngest president in history, aged 43, and the first Catholic president, making his election even more historic and feeding into the notion that his presidency would somehow be different.

The couple’s early days in the White House reflected a new visible level of glamour. The Kennedys went on trips via private jets to Palm Springs, attending and hosting lavish parties that boasted royalty and celebrity guests. Famously, these guests included members of the ‘Rat Pack’ such as Frank Sinatra, adding to the image of the Kennedys as young, fashionable and fun.

President Kennedy and Jackie attend a production of ‘Mr President’ in 1962.

Image Credit: JFK Library / Public Domain

Building the myth

The term Camelot has been used retrospectively to refer to the Kennedy administration, which lasted between January 1961 and November 1963, capturing the charisma of Kennedy and his family.

Camelot was first publicly used by Jackie in a Life magazine interview, after she invited the journalist Theodore H. White to the White House just days after the assassination. White was best known for his Making of a President series about Kennedy’s election.

In the interview, Jackie referred to the Broadway musical, Camelot, which Kennedy apparently listened to often. The musical had been written by his Harvard schoolmate Alan Jay. Jackie quoted the ending lines of the final song:

“Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief, shining moment that was known as Camelot. There’ll be great presidents again… but there will never be another Camelot.”

When White took the 1,000-word essay to his editors at Life, they complained the Camelot theme was too much. Yet Jackie objected to any changes and herself edited the interview.

The immediacy of the interview helped cement the image of Kennedy’s America as Camelot. In that moment, Jackie was a grieving widow and mother in front of the world. Her audience was sympathetic and, more importantly, receptive.

Jackie Kennedy leaves the Capitol after the funeral ceremony alongside her children, 1963.

Image Credit: NARA / Public Domain

It wasn’t long before the images of Kennedy’s Camelot era were being shared and reproduced throughout popular culture. Family photographs of the Kennedys were everywhere, and on television, Mary Tyler Moore’s Dick Van Dyke Show character Laura Petrie often dressed like the glamorous Jackie.

Political realities

Like many myths, however, Kennedy’s Camelot was a half-truth. Behind Kennedy’s public image as a family man lay the reality: he was a serial womaniser who surrounded himself with a ‘cleaning crew’ who prevented news of his infidelities from getting out.

Jackie was determined to ensure her husband’s legacy was not one of misdemeanours and unfulfilled promises but integrity and the ideal family man.

The myth also glossed over the political realities of Kennedy’s administration. For example, Kennedy’s election victory over Vice President Nixon in 1960 was one of the narrowest in presidential history. The final result showed Kennedy won with 34,227,096 popular votes to Richard Nixon’s 34,107,646. This suggests that in 1961, the idea of a younger celebrity president was not as overwhelmingly popular as the Camelot narrative suggests.  Listen Now

Listen Now

In foreign policy, during his first year as president Kennedy ordered a failed overthrow of the Cuban revolutionary leader, Fidel Castro. Meanwhile, the Berlin Wall went up, polarising Europe into the Cold War ‘East’ and ‘West’. Then in October 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis saw the US narrowly avert nuclear destruction. Kennedy may have had a flexible response but his presidency also featured diplomatic failures and stalemates.

A New Frontier

In 1960, the presidential candidate Kennedy had made a speech describing America as standing at a ‘New Frontier’. He referred back to the pioneers of the west who lived on the frontier of an ever-expanding America and faced the issues of establishing new communities:

“We stand today on the edge of a New Frontier – the frontier of the 1960s – a frontier of unknown opportunities and perils.”

While more of a political slogan than a distinct set of policies, the New Frontier program embodied Kennedy’s ambitions. There were some great successes, including setting up the Peace Corps in 1961, creating the man-on-the-moon program and devising the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, signed with the Soviets.

However, neither Medicare and federal aid to education got through Congress and there was little legislative progress for civil rights. Indeed, many rewards of the New Frontier came to fruition under President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had originally been tasked by Kennedy with getting the New Frontier policies through congress.

President Kennedy delivering a speech to Congress in 1961.

Image Credit: NASA / Public Domain

These factors do not diminish the successes of Kennedy’s short presidency. More so, they highlight how the romance of Kennedy’s Camelot removed nuance from the history of his administration.

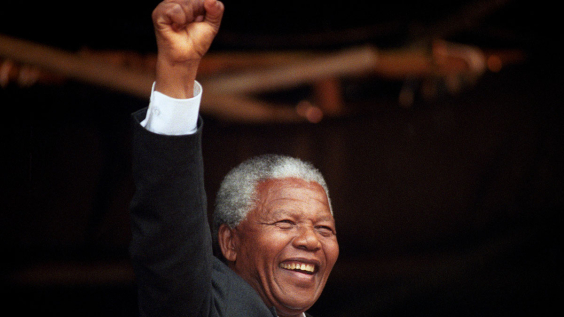

Perhaps the myth is more useful when examining the years following Kennedy’s assassination rather than his years of presidency before it. America held onto the narrative of Kennedy’s idyllic presidency as the 1960s presented the challenges that Kennedy’s New Frontier speech had alluded to: the continuation of the Cold War and escalation of conflict in Vietnam, the need to address poverty and the struggle for civil rights.