The landscape of Britain has been shaped by thousands of years of human endeavour. Every generation leaves a mark – communities travelling through the wilderness, modifying the terrain as they went. Every footfall, every animal hoof, and every wooden wheel carved tracks into the earth. If you know where to look, you can still find these ancient ways crisscrossing Britain today, offering an opportunity to follow literally in the footsteps of our ancestors.

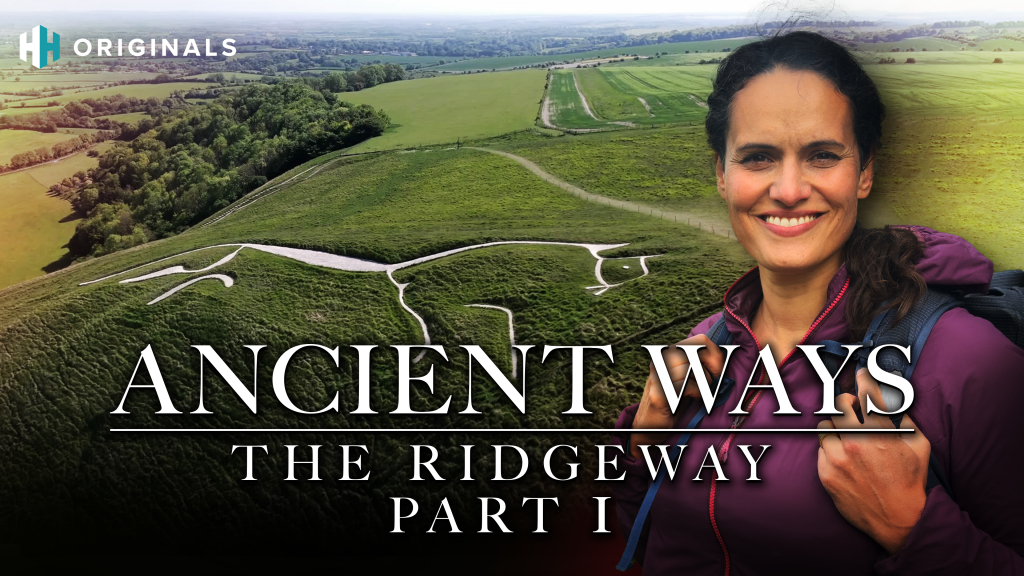

In the two-part special Ancient Ways: The Ridgeway, anthropologist and keen hiker Mary-Ann Ochota tracks these prehistoric pathways along the Ridgeway – one of England’s oldest routes and a true ‘Stone Age Highway’. Join Mary-Ann as she visits some of the trail’s most iconic landmarks, from the enigmatic Uffington White Horse to the megalithic wonders of Avebury Henge.

A braid of routes

Five thousand years ago, the Ridgeway wasn’t a single, officially designated path; it was a braid of multiple routes heading roughly in the same direction across the high ground. While the modern Ridgeway National Trail spans 87 miles from Ivinghoe Beacon in Buckinghamshire to Avebury in Wiltshire, the original prehistoric route stretched much further – running from the Wash in Norfolk, southwest all the way to the Dorset coast.

“To understand the past,” Mary-Ann explains, “we need to understand how people moved and why.” The Neolithic people who first used this route – the same builders responsible for Stonehenge – were farmers who raised cattle and sheep. They travelled for trade, pilgrimage, and community events, using the high chalk ridges to stay above the marshy, wooded and often dangerous valleys below.

Production shot – filming on The Ridgeway

This path forms a distinctive white ribbon through the landscape. This chalk was formed 145 to 65 million years ago, in the age of the dinosaurs, when the area sat near the equator under a subtropical sea. Created by the compacted skeletons and shells of ancient sea creatures, this unique geology now supports a rare ecosystem of specialist plants, insects, and birds.

Production shot from The Ridgeway

Uffington: the horse and the hillfort

Mary-Ann begins her journey at Uffington Hill, a site thick with prehistoric treasures. At the summit sits a massive Iron Age hillfort, half a mile in circumference. But the true mystery lies beside it: the Uffington White Horse.

At 111 metres long, this semi-abstract ‘geoglyph’ is the oldest hill figure in Western Europe. National Trust ranger Andy Foley explains that while it looks like a simple chalk drawing, it is actually a complex feat of engineering. Trenches were dug a metre deep, backfilled with chalk rubble, and smoothed off on top.

Scientific dating reveals that the horse’s deepest layers are at least 2,500 to 3,000 years old. Created at the dawn of the Iron Age – coinciding with the introduction of domesticated horses to Britain – the figure was likely a tribal statement of status and power. Remarkably, the figure only remains visible because it has been scoured and cared for by the local community for three millennia. Andy suggests that the horse’s specific placement may indicate its care was initially connected to religion.

Mary-Ann Ochota with National Trust ranger Andy Foley at the Uffington White Horse

Image Credit: History Hit

Wayland’s Smithy

Walking west, Mary-Ann reaches Wayland’s Smithy, a burial chamber nearly 2,000 years older than the White Horse. This megalithic monument, dating to roughly 3,400 BC, is a ‘Cotswold-Severn’ type barrow, consisting of a stone edifice, an earthen mound over 100 metres long, containing a central passage with chambers inside to bury the dead.

Although seeming quite a straightforward burial site, archaeology reveals a complex history: a smaller timber-and-earth burial site existed here first. A century later, as farmers claimed territory more permanently, they constructed longer-lasting monuments to house the dead, including the massive stone edifice seen today. Curiously, historians believe the design was already ‘old-fashioned’ when it was built, suggesting the builders were attempting to claim a deep, ancestral association with the land to legitimise their presence.

Production shot of Mary-Ann Ochota filming at Wayland’s Smithy

Image Credit: History Hit

The site is steeped in Saxon legend. Historian and storyteller Jason Buck explains that the name comes from Wayland, the Germanic smith of the gods. Legend says that if you leave your horse here with a coin, the invisible smith will have it shod by morning.

Production shot – Mary-Ann Ochota shares a cuppa with historian and storyteller Jason Buck as she sets up camp for the night

Image Credit: History Hit

The Neolithic toolkit

After a night in a tent, Mary-Ann’s journey continues from Hackpen Hill to Fyfield Down, where she uncovers the reality of prehistoric industry. Though they lacked metalworking, people at this time were using stone tools, flint tools, leather, bone, antler, and natural textiles. As Mary-Ann explains, stone tools weren’t just bashing two rocks together, “they were really sophisticated craftspeople. They really understood their materials.”

In the Neolithic period (4,500 BC to 2,300 BC), stone axes were one of the key components in their toolkit – the ‘Swiss Army Knives’ of the age. While flint axes were used for everyday timber work, ‘posh’ versions of axes made from carefully chosen polished volcanic and sedimentary stones were symbols of elite status. These were either ground into shape or, in the case of flint and chert, fashioned through ‘knapping’ – a precise process of striking the stone to chip away the edges. To achieve a mirror-like, glass-smooth finish, craftsmen would rub the piece against abrasive sarsen stones for days or even years to get it perfectly polished.

Remarkably, these stones weren’t local; analysis shows that rough-cut blocks for polished axes were quarried across the UK – from the Lake District to Cornwall, even as far as Northern Ireland – and traded along the Ridgeway.

‘Polisher stone’ at Fyfield Down

Image Credit: History Hit

Mary-Ann visits a ‘polisher stone’ at Fyfield Down – a sarsen boulder featuring deep, smooth grooves used to create, sharpen and shape the edges of the axe. These marks were created by humans sitting for hundreds of hours, grinding stone axe heads against the rock using wet sand to achieve a mirror-like finish. Standing by the stone, one can almost feel the presence of the craftsmen who laboured here 5,000 years ago. It’s unknown why this particular sarsen stone was chosen above the others for this purpose, but it is seen as a treasure of the Neolithic age.