Japan’s Edo period spanned over two centuries, from 1603 to 1867, during which the country was ruled by the Tokugawa shogunate. Japan implemented isolationist policies, largely cutting itself off from the outside world and banning foreign visitors (known as sakoku), yet the economy and arts prospered in the same period.

Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868 which overhauled the feudal system that had governed the country for centuries, Japan was once again open for trade and travel with the wider world, and there was a huge amount of enthusiasm for Japanese art and culture in Europe. The artistic legacy of the Edo period continues to captivate and inspire people the world over to this day, and Japanese art remains highly recognisable and in demand.

Flourishing arts

In the 17th century, the Japanese merchant class grew dramatically and they began to use some of their newfound wealth and leisure time to patronise artists, helping to create a blossoming leisure sector.

The search for pleasure and enjoyment became known as ukiyo (the floating world) and interest in this sector helped develop an area of Edo (now known as Tokyo) called Yoshiwara, which was essentially a red light district.

Painting, printing, theatre, music, literature and professional female entertainers were all part of this new cultural boom. Urbanisation and local tourism also helped develop these industries.

A set of three ukiyo-e prints depicting Osaka’s bustling shipping industry. by Gansuitei Yoshitoyo. 1854–1859

Image Credit: Yoshitoyo Gansuitei (芳豊 含粋亭) aka Utagawa Hokusui (歌川北水), (1830-1866)., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Woodblock printing

Known in Japanese as ukiyo-e (literally, pictures of the floating world), a craze for woodblock printing swept Japan in the late 17th century, and it continued to be an extremely popular genre right through to the 19th century. Traditionally depicting subjects like geisha, kabuki theatre and elements of life in the pleasure districts, they grew to encompass landscapes and scenes from folklore too.

The most famous Japanese woodblock print is The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831), pictured below, by an artist called Katsushika Hokusai, which was part of a wider series called Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. By the late 18th century full-colour prints were standard, but they were still complex affairs, involving artists, carvers, printers and publishers in order to generate the finished product.

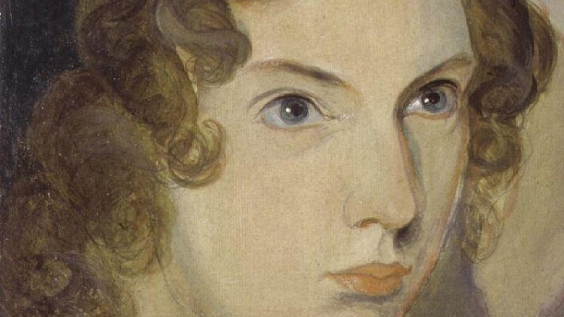

Katsushika Hokusai

Hokusai has become synonymous with the art of Japanese woodblock printing. Born in Edo in 1760, his father is thought to have been a mirror maker to the shogun, and Hokusai learnt how to paint from an early age. After stints working in a bookshop and being apprenticed to a woodblock carver, Hokusai entered the studio of the prominent artist Katsukawa Shunshō.

Over the subsequent decades, Hokusai made a name for himself, working for assorted masters of their crafts and experimenting with his own ideas and creative practice in the process. He developed a distinct style and was notoriously particular about his work.

Despite being most famous for his landscape prints, Hokusai also created several volumes of manga, collections of erotic art and whimsical, imaginative illustrations drawing on folklore and legend from across East Asia and the natural world. With a career spanning over 7 decades, Hokusai produced over 3,000 colour prints, 1,000 paintings, hundreds of drawings and illustrations for over 200 books.

‘The Great Wave off Kanagawa’, Hokusai’s most famous print, the first in the series ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji’, c. 1829–1832

Image Credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Great Picture Book of Everything

In the 1820s, Hokusai was commissioned to create an illustrated encyclopaedia entitled The Great Picture Book of Everything. Although Japan lived largely in splendid isolation at that time, it kept strong commercial ties with China.

Chinese culture and art slowly found its way back to Japan, and ancient folklore and legendary historical figures proved inspiring for Japanese scholars, artists and religious leaders.

Despite having never left Japan, Hokusai’s drawings include figures and creatures from places like China and India, as well as mythical beasts. Collections like The Great Picture Book of Everything would have introduced Japanese people to a world far beyond the realms of their imagination, giving them a chance to travel without ever leaving the country.

Because encyclopaedias like this were picture-based rather than text-based they could be enjoyed by a very wide variety of people: from small children up to the illiterate elderly.

However, The Great Picture Book of Everything was never published. The 103 original drawings and prints that it would have comprised of were boxed up and largely forgotten about, appearing at auction in 1948 and resurfacing in 2019, when they were purchased by the British Museum.

Listen Now

Listen NowJaponisme

Japanese items were extremely highly prized in Europe: often made with exquisite craftsmanship, amazing attention to detail and imbued with a level of rarity and exoticism, they were sought after by the upper classes.

After the forced re-opening of Japan in 1854, Europe began to go crazy for Japanese items. Known as japonisme, art and objects from Japan flooded the market. Woodblock prints like those of Hokusai influenced Western artists with their use of asymmetry, foreshortening and flat colour. Lacquerware and porcelain of the highest quality could be found in the most fashionable homes and Japanese gardens began to make an appearance in Europe.

Although the Edo period was effectively over by the time Japan re-opened, the era of japonisme gave Edo-period art, particularly that of Hokusai, international recognition and helped create a legacy which lasts to this day.